What is Eurovision in 2021?

Everybody is smart, and only I am insane: a look into the Song Contest, Turkey, and the "apolitical character" of the show

Every year, the Eurovision Song Contest follows a certain motto. This year’s is Open Up, which, at this point, sounds less like a motto and more like a demand from a lot of people and government parties across the continent. This would make the second summer with COVID-19, and between rising vaccination percentages and slowly warming weather, being locked at home seems ridiculous. People deserve to go on vacations, shop in malls, drink in pubs, have social interactions again - without worrying about anything, people want normalcy after a strange one-and-a-half years. From this angle, the Eurovision Song Contest, held after a year’s delay in Rotterdam, Netherlands, must have felt like a step towards life B.C (Before Corona), a view that Peter Urban commentating for the German national television ARD represents: “We deserve Eurovision - let’s forget about the pandemic and the stress for a night.” He isn’t the only one: during voting, presenters across several countries thanked the Netherlands and the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) for hosting a show that brought back some “normalcy that can bridge all differences”.

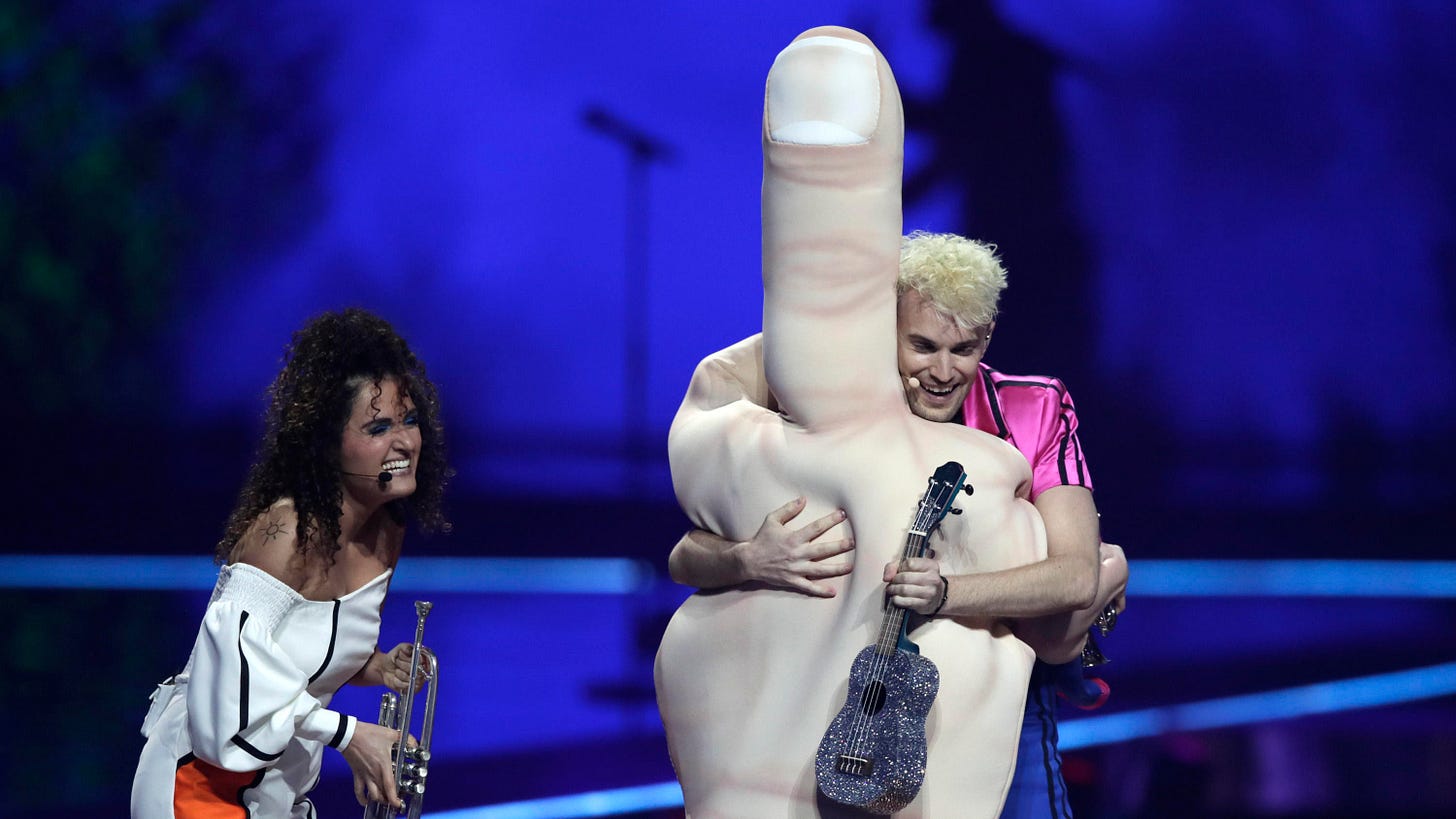

Let’s keep the “we” suspended for a moment and talk about the show. The songs certainly were opened up to the American pop market, to say the least - pop heard elsewhere, performed by stronger personalities. The ones that weren’t fell on either spectrum of greatness and garbage. Germany and the UK received nul from both public and jury for lazy songs and terrible performances - but sponsors get to the final no matter what. Italy’s entry, ZITTI E BUONI, was a good song and a worthy winner, reminiscent of Arctic Monkeys but with a stronger swagger. Go_A, performing for the Ukraine, performed SHUM, a folkloric song with thunderous techno beats and a frontwoman so captivating not even twinkling running men in the background could distract from her. It’s one of the strangest entries in recent Eurovision history, possibly only rivaled by Belgium’s 2003 entry Salomi (the only song in the history of ESC, to my knowledge, to be sung in a completely made up language). SHUM, alongside Discotheque for Lithuania and 10 Years for Iceland, make up a solid amalgamation of the imagined Eurovision internet Millennials and Zoomers have: bizarre, regional, and banging. It is the sieben-sieben alulu, the babushkas, and the epic sax guy.

Between performances, the show featured several pee breaks— I mean a cover of Sia’s Titanium, as well as performances from past winners on different roofs, and a bland inbetween sketch about ESC makeup and how presenters dress for the douze points (hint: lots of cleavage). Iceland’s presenter was a nod to the 2020 film Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga, a film about… Eurovision. Lots of people trying their hand at Dutch because tonight, we all love each other. Cyprus and Greece awarded each other twelve points. Neighbors in the Eastern Bloc and Scandinavia get points no matter what. It’s ESC night, alright. This isn’t the Eurovision of your memory, but it comes close to the only time besides New Year’s Eve where you were allowed to stay up all night long.

Ahead of the Contest, The Independent has declared the Song Contest to “stick to its values” in an “illiberal” world in this article. They refer to Belarus, which was disqualified this year because their entry, Ya nauchu tebya (I’ll Teach You) would “instrumentalize or brought to disrepute” the contest, with an Orwellian-type chorus. Die German Tagesschau reports that the organisators thought that Belarus’ entry “questioned the apolitical character” of the show. Armenia did not send an entry due to Karabakh, but Azerbaijan - the other, winning side - did, with a frankly horrible song and an Ariana Grande copy of a copy. Israel sent an eighteen-year-old girl currently serving in the IOF who sang about peace titled Set Me Free. Israel won for the fourth time in 2018 with Natta’s Toy, thus also hosting the show in 2019. Israel has participated in the show since 1973. “Israel” is an illegitimate nation whose government is colonizing and ethnically cleansing the indigenuous Palestinian people - and has been since 1948.

Turkey participated in the song contest from 1975 to 2012, resulting in a total of 34 entries. The first time I was made aware of it was 2003, when Sertab Erener - a popular figure even back then - was chosen to represent Turkey with Everyway That I Can. I remember hearing the guitar-driven pop song Kumsalda (At the Beach) from her before and, to a six-year-old, it was enough to love her. And besides, it was Turkey. Türkiye! I wanted us to win. All I remember of that year’s Eurovision was her performance, us trying to vote for her by phone, the tediously long voting process - back then, countries would announce every point from 1 to 12 - and being bewildered that I was allowed to stay up until 1am. Everyway That I Can: The bass runs deep in this song, the darbouka serves as drums, the chorus soars high, the vocals are on point, the outfits are appropriately flowy, and it has a strong oriental flavor throughout. It is a great song in general, and one of Turkey’s best entries overall. And it won.

From there, year after year, I moved with a simple principle: the Turkish entry was always the best, and every country should give it 12 points. (Exceptions proved the rule.) Every year, during the voting process, I would chant: “Türkiye, Türkiye, Türkiye”, no matter the country, no matter who had bad geopolitical relationships with Turkey or just didn’t care for us. The precedent was set and I would not budge for less than a second #1! For Real, Rimi Limi Ley, Superstar, Shake it up Shekerim, Deli, Düm Tek Tek, We Could Be The Same, and Love Me Back in 2012 (Yüksek Sadakat’s 2011 entry, Live It Up, did not make it to finals) - being a Turk rooting for Turkey at the time meant you were almost always going to get a high quality song, or at the very least a solid blend between pop sensibilities and Middle Eastern melodies. Every year I would wonder who they would send next, until we didn’t.

In 2013, Turkey’s reasoning for abstaining from the ESC (via then cultural minister Bülent Arınç) was that the voting system was unfair; that in addition to the “Big Five” (Germany, UK, France, Spain and Italy) entering the final without a qualification since 2000, the “voting blocs” prevented Turkey from placing where they wanted to. In fairness, since 2003, Turkey has never placed awful after Sertab Erener, and diaspora votes ensured Turkey would never fall off to the bottom. Nevertheless, it’s a valid criticism to make. By the time 2019 rolled over with a new system that separated televoting from the jury (or at least made the difference more visible), TRT’s president Ibrahim Eren said it was “Conchita Wurst”, 2014’s winner for Austria and a drag queen, which “perverted Eurovision’s values”, would be “impossible to air” when children were watching, and only if the EBU corrected its “mental confusion” would Turkey return. The “Oh no, the gays!” criticism feels frankly silly considering ESC’s history (For instance, in 2003, Austria’s presenter was at the Life Ball, a charity event against AIDS hosted by a gay man. Austria gave Turkey the decisive points to win over Belgium’s entry Salomi). So the question of when Turkey returns has now, in 2021, become a big if, if not entirely redundant. I frankly don’t think this administration will return to the EBU or send in anything to Eurovision ever again. Still, when maNga, turning second in 2010 with a song about and titled We Could Be The Same, tweeted they would gladly represent Turkey a second time in 2018, people immediately jumped onto the possibility — to the point where maNga had to clarify later that they would like to, not that they will. In 2020, Sertab Erener was asked what she thinks of Turkey’s return to the Eurovision Song Contest. She said:

I think we definitely should return. It’s one of the sweetest contests in the whole world. A contest with a long past, that contains culture. I think culture is everything. Nations and individuals should aim to share their culture. Eurovision is a stage where we can show our culture and music to the world. It’s a very nice arena and a very fun show. That’s why we should always be in.

For a BBC Turkey retrospective this year, Şebnem Paker adds that at this point, Turkey should’ve been able to express itself in art. And further: “You can’t criticize a system if you’re outside of it.”

I watched 2004’s For Real earlier: a ska-flavored rock piece by rock group Athena. The amount of Turkey flags waving in the audience, the loud cheers, the music that is so intimately familiar to me - all of it is so vivid and overflows me with a feeling I have not felt in a long time. It’s always an overwhelming image, but in 2021 and with tattered internal politics, the whole thing becomes something more potent. It’s the image of a Turkey, united.

Between the late Kayahan in 1990 and all the way until Sertab Erener 2003, Turkey - through national television TRT - did not send in local popular acts.

Turkey’s 1990 entry, Gözlerinin Hapsindeyim (I’m in the Prison of Your Eyes) is one of Kayahan’s best known songs. With its prominent acoustic guitar, as well as an accordion and brass throughout, and a very lovely vocal melody, it’s a perfect representation of Turkey in the turn of the 1990s by an acclaimed singer-songwriter of his time and country (of all time, in fact), and placed 17th of 21 countries that year. Was it because Kayahan is a man and not an attractive woman? Is it the band setup? In either case, the songs and artists TRT did send in afterward sound like the copy of better English/French songs; outside of ESC, Turkey was receiving its first private television channels; Turkish pop had its boom; Turkey was doing poorly in the ESC anyway, and so, Eurovision was no longer the family-and-relatives event of the 80s.

All this changed when 1996’s participant, Şebnem Paker, returned to represent Turkey again in 1997. Dinle (Listen) placed just behind the United Kingdom and Ireland. It would set a precedent for everything to come from Turkey. Dinle itself is a very Turkish piece. A saz is the first thing you hear, then the ney, a darbouka, and in the middle of it all, a wide-eyed, black haired girl that swings her hips languidly. The chorus is a winner, but the whole song is a well-crafted pop piece. Only now it’s Middle Eastern.

Buoyed by the third place, the female acts sent afterward tried to replicate this success. Here you see 1999’s entry: on an average Turkish pop song, Tuba Önal is dressed in a way that I would register as “dansöz” (bellydancer) but regardless undoubtedly reads Oriental. So are her female dancers.

2000’s Pinar Ayhan and the S.O.S and 2002’s Buket Bengisu both went for Turkish salsa and finally, 2003’s Sertab Erener’s win spearheaded what then became the standard template for all female acts to represent Turkey. Once TRT found it, it was determined to ride it all the way through: with Rimi Limi Ley (2005, 13th) and Süperstar (2006, 11th) representing two ends of the same spectrum, then with a man surrounded by female dancers in 2007’s Shake it up Shekerim by Kenan Dogulu (4th), and 2009’s Düm Tek Tek (4th) by Hadise just flat out featuring belly dancing: this is the ethnic performance for the West. The Middle East, right at the European population’s fingertips. The Oriental for easy consumption. A very similar trick was also done by Turkey’s neighbor, Greece: take Shake it by Sakis Rouvas in 2004, and My Number One in 2005 going to sirtaki in between chorus and verse. My Number One, the winner of that year, has been shown in every ESC retrospective since.

Turkey’s entry in 2005 was Gülseren. She was criticized from the start by the song Rimi Limi Ley, a song selected by TRT to represent the country. The song includes folkloric elements and made Turkey return to Turkish entries. It’s a fine song - not great, but not bad either. It got #13 of 24 and marked an entire nation disappointed after two top 5 placements. Years later, Gülseren would say that not only was she humiliated by crew (notably celebrity Armağan Çağlayan) about her body image, she was “tossed away” by TRT, and suffered from depression and financial problems after her turn on the Eurovision Song Contest. Placing thirteenth - after Erener and Athena - was a major disappointment to the country as a whole.

The artist and song selected after Gülseren, Sibel Tüzün’s Süperstar, was originally written by Tüzün in English before TRT forced her to rewrite the song in Turkish and barred her from singing English. Yet for the finals, in skimpy clothing and shaking her hips, she sang the chorus after the break in English (which, sure enough, TRT fined her for) - Turks in Youtube comments now speculate her singing in English would’ve made her win. Another person’s comment reads: “Her accent is godawful. The song is bad.” (Echoing my sentiments fifteen years ago; I think the song is fine if a little wonky in either language, and not winner material). Lordi won in 2006 with Hard Rock Hallelujah.

The male representatives of this period I didn’t mention thus far are rock acts (2001’s Sevgiliye Son, turning eleventh, is a by-the-numbers ballad so we can ignore it). maNga’s 2010 entry, We Could Be The Same, features a strong stage direction (with strobing lights) and an all English rock song about “we” being the same for the night, no matter what “they” say. The “we” and “they” in question could be anyone; it’s so universally written that part of what brought this song to second place has got to be its all-purpose lyrics. To these Turkish ears, hearing a Turkish man sing about “we” potentially being the same, in a show that - while no longer only watched by that continent - targets and hosts European countries, will always read as Turkey and Europe. For that matter, “they” is also Europe. Turkey and Europe could be one, if Europe stopped listening to its dissidents. Can Bonomo’s Love Me Back in 2012 goes a little further with the Turkishness - the dancers run the gamut of Turkish folkloric dances in the second chorus - while singing about ships and sailing to the sea. It’s a fun song and a great performance, scoring Turkey a 7th place finish. Oh-oh / Baby don’t shut me down / Give me all the love I need, and I’ll be gone, Bonomo sings, and You love me and you know that / baby, don’t you lie / Like me like I like you and say nananana. There’s something oddly symbolic about it now: the final entry of Turkey with this title, this presentation, and a loud Haydi shouted for good measure, make a satisfying run of a country that only hit its stride in its last ten years of competing. It might as well be one of two entries that’s less Oriental and more Turkish.

The other act is 2008’s Deli (Insane) by rock act Mor ve Ötesi. In its performance, all four members are dressed simply in black, while giant dwarves leer in the background behind them. If Turkish is a foreign language to you, then all that will seem strange is Harun Tekin’s haunting, slightly unhinged stares at the camera, with a mocking smile to match. Everything else is a solid rock performance, complete with fireworks and the band jumping as they perform the stunning outro. The word drops in the bridge: “One half of mine (is) insane, one half smart / Four sides of me smart, one insane / Everybody is smart, and only I am insane”. The chorus is as follows:

Raise me up

Don’t make me cry

Where is the love

that you brag about?

Raise me up

Don’t betray me

Don’t waste my time

with false dreams

As frontman Harun Tekin says ahead of the performance, if they were successful in their native language, it would reassure Turks that they have “many friends who understand them”.

In the Turkish Millennial imagination - for all of Turkey - Eurovision isn’t bizarre or colorful. At least, not primarily. It’s fun, yes. But for Turks, it’s first a showcase of our culture, and second a challenge we have to win. If acts like Kayahan didn’t get what we think it deserved, then it’s Europe’s fault for not valuing us. Other host countries send in bad entries to avoid a second time of winning; Turkey sent in Athena and had every intention of winning again. The push-pull effect of needing Turkey to be validated by the West, and pouting when it is not, doesn’t seem odd when you consider this is woven into the very fabric of Eurovision. Viewers stop thinking about politics, they assume. Just memes, right? But for Turks this is still politics - foreign politics, in fact. The people that want Turkey back in the Eurovision Song Contest are still wondering how to polish up the presentation of a country that progressively nosedived into chaos. Recall Arınç: the expectation was getting the goal we wanted, meaning #1, meaning a chance to host the country the year afterward and show the world Turkey - a Turkey that does not exist, has, in fact, never existed.

Because Eurovision Song Contest is not sharing cultures so much as selling a fantasy. Selling Turkey’s image, making it enticing and exotic and worth spending money on, is the message behind Hadise, or Sibel Tüzün, or even Şebnem Paker. It is also the message of Love Me Back or We Could Be The Same. Only when Turkey understood that, it did well in the competition. Because no one outside of us cares, or would care, about a friendly-looking man playing a locally popular song. But people care when they know what to get, which is bellydancing and a continuation of the collectively imagined Ottoman Empire, or flat-out familiar rock you only need to jam your head to. You’re allotted three minutes time, five people on stage, and a year’s worth of preparation for an advertisement. Turkey recognized it can promote elsewhere, through other means, and with far better results. Eurovision is no longer needed to this government; it’s selling its fantasy to other people of the nation. Change in policies.

I talked so much about Turkey because I’m Turkish. But don’t get me wrong: the selling fantasy part, the promotion, all of these countries do. Not just the Eastern European country of your choice, and certainly not just (but most egregiously) Israel: all of these countries. What is it that Spain’s general participation sells when, on any other day, migrants are pushed outside the border with tear gas? What is it that France sells by sending a singer with Serbian-Iranian descent when the country’s Islamophobia is on the rise? What is it that Germany sells with a song not caring about “haters” when, on any other day, it claims immigrants have "imported” antisemitism? And Austria, on its way to build an autocracy: what does it sell when Vincent Bueno asks: Is this what you wanted?

These are all trick questions. The song not saying anything, the song being “apolitical”, and a non-white artist representing a majorly-white country, do not magically absolve the promotion of the country, and more specifically the country’s government, through the song.

So the real question is: what is Eurovision in 2021? Is it worth it, in 2021, to watch a fantasy play out like a memory, when even the show knows it’s no longer what you remember it being? When it was never, and will never be, the show that you remembered in the first place?

The issue isn’t even a “respite from the pandemic” here. Eurovision Song Contest hosts first-world and some second-world countries that will end up with massive financial losses by the end of the pandemic, but whose people are - as of now - doing far better than, say, India’s or Brazil’s. The issue is what the Eurovision Song Contest is seen as. A beacon against an “illiberal” world, when Israel is still allowed to participate like the European cultural outpost it is treated as? Who is the “we” that “deserves” the Eurovision Song Contest? Is it white audiences that on any other day just do not care that the show is a nationalist power fantasy? Is it a section of the LGBT community that thinks the contest is a celebration of their sexualities, disregarding that other queer, non-white people elsewhere are suffering?

Only at best is the Eurovision Song Contest a night’s worth of escapism. Mostly, increasingly, and especially in 2021, it’s oppressors whitewashing their hands off crimes. Next year, Italy gets the chance to promote the country again - whether the country’s self-promotion is overt or not, it is still promoted just by hosting a beloved show. And everybody will whitewash their hands again. “Not of political character”, though, am I right?

In 2019, when the Eurovision Song Contest was hosted in Tel Aviv, Israel, Icelandic band Hatari displayed scarves with the Palestinian flag on it as an act of protest (despite the flag being banned since 2016. The Icelandic broadcaster was fined for this). This was at the height of a worldwide BDS (Boycott-Divestment-Sanctions) campaign to boycott the Eurovision Song Contest - as in, not attending and watching it - which, that year, drove tourist numbers of the hosting country down to just five thousand local attendants compared to Lisbon’s ninety thousand. So what’s the issue with Hatari’s performance? They were criticizing the system from the inside, right? Well, except the whole point was not going. This is what the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel had to say to Hatari’s criticism within the system:

“Palestinians are calling on all Eurovision contestants to withdraw from the contest in apartheid Tel Aviv. This includes Iceland’s entrant Hatari, in particular, who are on the record supporting Palestinian rights.

“Artists who insist on crossing the Palestinian boycott picket line, playing Tel Aviv in defiance of our calls, cannot offset the harm they do to our human rights struggle by “balancing” their complicit act with some project with Palestinians.

“Palestinian civil society overwhelmingly rejects this fig-leafing, having learnt from the fight against apartheid in South Africa.

“While we appreciate gestures of solidarity, we cannot accept them when they come with an act that clearly undermines our nonviolent human rights movement. The most meaningful expression of solidarity is to cancel performances in apartheid Israel.

“We appeal to all Palestinian artists to refrain from organizing any activities with artists who violate the guidelines of the cultural boycott of Israel.”

I will not be watching the Eurovision Song Contest in the coming years. At least not until Turkey comes back, in which case, I know I’ll be roped back into seeing it, forced, for one night, to watch everybody play pretend.